Your health care team will take a sample of your bone marrow to check for multiple myeloma cells. They may also order x-rays, CT scans and other imaging tests.

Your doctor may prescribe medicines that target specific chemicals on cancer cells. You might get idecabtagene vicleucel (Abecma) or interferon.

What is myeloma?

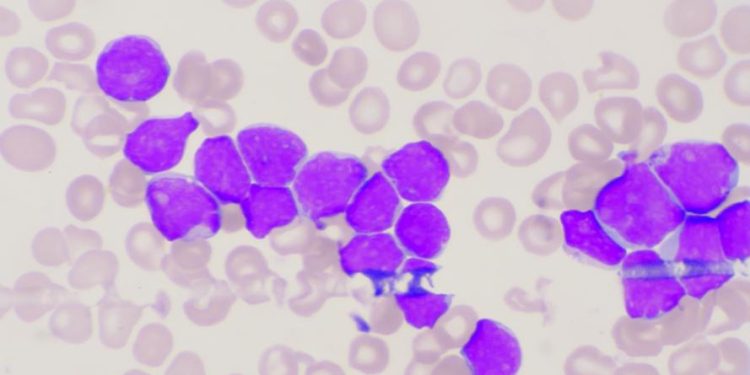

Multiple myeloma is a type of blood cancer that starts in plasma cells. Plasma cells are a type of white blood cell that makes antibodies (also called immunoglobulins) to help fight infection. In myeloma, plasma cells start to change and produce too many abnormal antibodies. These abnormal antibodies build up in the bone marrow and crowd out healthy blood-forming cells. They also cause other medical problems. These problems include frequent infections (because the myeloma cells crowd out healthy white blood cells that normally fight infection) and high calcium levels in the bloodstream, which can damage kidneys. Some people with myeloma have bones that are weakened and break more easily.

A health care professional can find multiple myeloma using blood tests and other diagnostic tools. The myeloma cells make proteins in the blood, which show up on lab tests. The tests can also find one of the abnormal proteins, called paraproteins, in a sample of urine. The body gets rid of the rest of the myeloma cells and the light chains of the paraproteins in the blood, a process called renal clearance.

Some people with myeloma don’t have any symptoms. Others have a low risk of cancer and don’t need treatment right away. Your age, the stage of myeloma and the genetic makeup of your cancer cells are important factors in deciding what treatment to use.

If you have myeloma, your doctor will prescribe medicines that help control the cancer and treat your symptoms. Some of these medicines attack the cancer cells directly or target proteins involved in the growth and spread of the cancer. Other medicines slow the production of new myeloma cells or boost your immune system. Research is ongoing to develop even more effective drugs for myeloma. Your hematologist or oncologist may suggest that you join a clinical trial to try new treatments. You can learn more about these trials by asking your doctor or visiting the website of the National Cancer Institute. The website offers a list of clinical trials in your area.

Symptoms

Some people with multiple myeloma do not have symptoms at all. This happens because the cancer is very slow-growing and may not have reached a critical mass. It also depends on the level of paraprotein in the blood. Some people who have a low level of the protein in their body will not need any treatment at all. Some people who have a high level of the protein in their blood will need more treatment.

Myeloma symptoms are caused by a build-up of plasma cells in the bone marrow and a high level of paraprotein in the blood. Symptoms include bone pain, especially in the back and ribs; a very high calcium level, which can lead to kidney problems; anemia, because multiplying abnormal plasma cells crowd out normal blood-forming cells and leave not enough room for red blood cells to grow; and a low platelet count, which stops your blood from clotting normally. This can cause nosebleeds, bleeding gums or a rash of tiny red spots on the skin (petechiae).

Multiple myeloma cells can also make too much antibody protein (immunoglobulin), which can damage the kidneys as it passes from the bloodstream into the urine. It can also cause the bones to weaken, which can make them break easily and often leads to pain in the ribs and spine. The weakened bones can also develop small holes in them, which are called lytic lesions and are seen on X-rays. The cancer can also lead to a lack of infection-fighting white blood cells, which makes you more likely to get infections.

In some cases, multiple myeloma can cause the spinal cord to become compressed, causing a spinal cord injury and serious symptoms like weakness in the legs, arms, or breathing. This is an emergency and needs to be treated as soon as possible.

People with multiple myeloma are usually managed by a team of specialists that might include a GP, a haematologist (specialist in diseases of the blood and lymphatic system) and a radiation oncologist. They might be given pain medicines or other treatments to control their symptoms and help prevent the cancer from getting worse. They will have regular blood and urine tests to look for signs of myeloma.

Diagnosis

To diagnose multiple myeloma, your hematologist-oncologist will need to carry out a number of blood tests and scans. These will help them find out if your cancer is localised or widespread in the body (stage). You will also have a physical examination to check how well you are feeling.

Myeloma develops when the DNA of plasma cells becomes damaged and these abnormal cells start to grow and multiply. They then release a large amount of one type of antibody called paraprotein. This is detected in the blood and urine and it helps doctors identify myeloma.

A bone marrow biopsy will be needed to confirm the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. This involves inserting a needle into a bone, usually in the pelvis, and taking a small sample of bone marrow (where all blood cells are made) to examine under a microscope. This is done using a local anaesthetic. You will also have a blood test called the serum free light chain assay and another test for a protein called beta 2-microglobulin. These proteins are produced by myeloma cells and they are not normally present in the body. They help doctors decide what stage myeloma is and how serious it is.

Other tests that may be done include the complete blood count and the serum protein electrophoresis. These tests check the levels of different proteins in the blood and are important because they help doctors determine the level of myeloma and its effect on normal blood cell production.

Your doctor will also check whether you have signs of thinning bones or any other health conditions. You may have X-rays of your bones to look for damage or thinning and an MRI scan of the bones, which is an imaging test that produces detailed pictures of soft tissue, organs and other internal body structures.

You may have a combination of treatments, including chemotherapy and medicines that target specific proteins or genes. You may also be offered a stem cell transplant, which involves giving you high doses of chemotherapy to destroy your existing plasma cells. This is followed by a transfusion of blood-forming stem cells to replace them, and this can restore your immune system and reduce symptoms.

Treatment

There are a number of treatments to help with myeloma. These include chemotherapy, stem cell transplants and other medicines. Your doctor will explain these in more detail. There are also supportive treatments to help control your symptoms, such as pain medications and radiotherapy. You may be able to take part in a clinical trial of new treatments.

Plasma cells are made in bone marrow and are part of your immune system. They make antibodies that fight infection and clot blood. When these cells become abnormal and divide, they produce more cancer cells. This leads to the build up of myeloma proteins, called paraproteins. These are found in the blood and urine.

Paraproteins can damage the kidneys and other organs and bones. They can also affect the way your body makes blood platelets. This can cause bleeding problems, such as nosebleeds and heavy periods. It can also lead to a condition called thrombocytopenic purpura, where the platelets are destroyed and do not clot the blood properly.

We use many different drugs to treat multiple myeloma, including bortezomib (Velcade), carfilzomib (Nelara), and melphalan (Alkeran). These drugs work together to kill cancer cells and reduce the amount of myeloma protein in the body.

If you are fit enough, your doctor might recommend a stem cell transplant. You have high doses of chemotherapy to destroy the myeloma cells and the stem cells in your bone marrow. Then you have new stem cells injected into your bloodstream through a drip. These are either your own stem cells or, less often, those from a donor.

A stem cell transplant can cure some people with myeloma. For others, it can control the cancer but not stop it from coming back.

You might have more treatment if you’re older; blacks have twice the risk of myeloma than whites. Or if you have a history of MGUS (monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance). You might be at more risk for myeloma if you have family members with it. Or if you have been exposed to radiation or chemicals, such as Agent Orange, or if you’re overweight.